GEOSCIENCE CURRICULA FOR 21st CENTURY

By E. Bruce Watson | December, 2007

Because of the rapidly changing nature of our field, many geoscience departments struggle with questions concerning the appropriate course content of today’s bachelor’s degree in geology. Those of us who completed our undergraduate education prior to 1980 probably have in common ~90% of our undergraduate geoscience courses, which would likely have included a “core” of physical and historical geology, mineralogy (2 terms), structural geology, sedimentation and stratigraphy, regional geology, paleontology, igneous and metamorphic petrology, sedimentary petrology, geomorphology, and a 6–8 week summer field course. Our predecessors designed this more-or-less standardized curriculum to provide essential knowledge in what were then largely disparate subfields of geology. All of these subjects were considered vital background for employment—mainly in the mineral and energy industries—and for advanced study in specialized graduate programs.

FAIRNESS IN EVALUATION MIRROR, MIRROR ON THE WALL

By Susan L.S. Stipp | October, 2007

This is my first editorial for Elements. When pondering over my own list of interesting topics, I was surprised that several people insisted I should write on their idea, “Women in Science.” Learning my place as a girl has been an issue from my earliest memory, but it is not something I think about every day. One assumes we live in a more equal world now. However, the mere fact that people think I should write about it makes it clear that it still is an issue and maybe deserves more thought. But can I say anything new? I wonder…

RISKING THE FUTURE OF GEOSCIENCE

By E. Bruce Watson | August, 2007

Earlier this year, the University at Albany (New York) moved to terminate its undergraduate and graduate degree programs in the geological sciences. Those of us who know “UAlbany” as the former and current base of some notable Earth scientists look upon this decision with bewilderment. Before passing judgment, however, we should note that the move was initiated by academic staff in the Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences and does not include elimination of the UAlbany Earth sciences curricula altogether: courses and degree programs in atmospheric and environmental sciences will continue.

SCIENCE AND THE POLICYMAKERS

By Ian Parsons | June, 2007

Richard Feynman’s ‘Minority Report to the Space Shuttle Challenger Inquiry’ has become a modern scientific legend. His brilliant, independent mind scythed through a mass of engineering detail, half-truth and wishful thinking and made the key observation that explained the destruction of the most complex machine ever made. He brought his conclusion home to public and politicians by a simple piece of showmanship involving a glass of iced water and a fragment of O-ring. NASA management estimated the probability of a shuttle failure at 1 in 100,000 or one failure if a shuttle lifted off every day for 300 years. Engineers close to the project estimated the risk of failure at 1 in 100. ‘What is the cause’, Feynman asked, ‘of management’s fantastic faith in the machinery?’

TEACHING, EXPLAINED

By Michael F. Hochella Jr. | April, 2007

Years ago, I had a rude awakening after I had finished teaching an undergraduate m i n e r a l o g y course. The petrology professor who taught the next course in the sequence told me that he had given a simple, short test (one that would not count towards the students’ grades) on the first day of class, not to check on my teaching, but to gauge the knowledge base of the students for more effective instruction— clearly a sound, educationally responsible idea. To his amazement, half of the students did not know the chemical formula of quartz. Many who thought they knew the formula wrote down “SiO4.” I was shocked. Only a month had passed between final examinations and my colleague’s test.

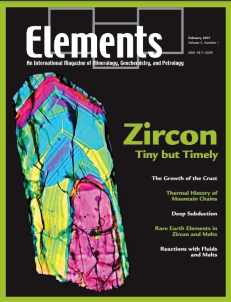

NOW YOU SEE IT, NOW YOU DON'T

By Ian Parsons | February, 2007

This issue of Elements tells the story of how tiny, rare crystals can give amazing insights into the history of rocks and the earliest days of our planet. The zircon on our cover is all of a third of a millimetre long yet contains evidence of several stages of growth, all of which could be individually dated using the U–Pb method. We can unravel the conditions of growth and crustal residence from isotopes of the common element oxygen and the rare element hafnium, more than a million times less abundant. Zircon provides a perfect marriage of mineralogy with geochemistry – a showcase for the brilliance of modern imaging and analytical methods.