v20n6 From the Editors

By Janne Blichert-Toft | December, 2024

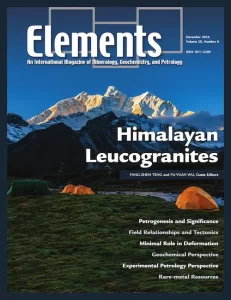

The Himalaya, the youngest and largest mountain range on Earth, is home to 10 of the world’s 14 mountain peaks higher than 8000 meters above sea level, including the highest Qomolangma Peak, widely known as Mt. Everest (8848 m). Leucogranites are exposed intermittently throughout over 2000 km along the crest of the Himalaya, forming on the summits or as an essential component of these high peaks. These Himalayan leucogranites are quintessential examples of crust anatexis associated with collisional orogenesis.

v20n5 From the Editors

By Janne Blichert-Toft, Sumit Chakraborty, Tom Sisson, Carol Frost, and Esther Posner | October, 2024

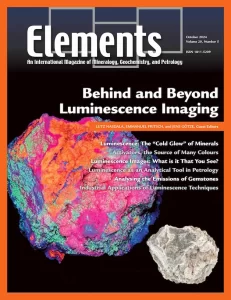

Luminescence images, typically obtained in optical or scanning electron microscopes, are in many cases extremely powerful and sensitive in unravelling defects, and revealing internal textures of minerals and mineral distribution patterns in rocks. The use of luminescence images in Earth sciences research is therefore widespread, and still increasing. However, the undisputed fact that such images can be used quite successfully even without knowing the causes of emissions, has created bad repute of luminescence as somehow unscholarly.

v20n4 From the Editors

By Janne Blichert-Toft, Sumit Chakraborty, Tom Sisson, and Esther Posner | August, 2024

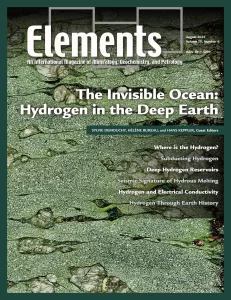

Hydrogen is the most abundant element in the universe and its distribution, transfer, and speciation in the deep Earth remain a fascinating topic of ongoing research. In this issue, we review the most notable recent discoveries constraining the hydrogen cycle in the deep Earth. “Hydrogen” here includes the element in all possible forms, oxidized as H2O molecules or OH groups in minerals and melts, as molecular H2, or as an alloy component in the core.

While the existence of a deep water reservoir in the transition zone of the mantle was hypothetical decades ago, it is now firmly established by the discovery of hydrous mineral inclusions in ultradeep diamonds.

v20n3 From the Editors

By Janne Blichert-Toft, Sumit Chakraborty, Tom Sisson, and Esther Posner | June, 2024

This “Cratons to Continents” issue of Elements provides insights into the multiple ways geoscientists explore the 45% of Earth history encompassed by the Hadean and Archean eons. The contributions provide examples of geochemical, petrologic, and geophysical approaches to unraveling the origin and evolution of continents. Our authors explore the craton to continent journey from the darkly shrouded mysteries of the Hadean from 4.6 to 4.0 billion years ago through the merely old Archean eon, 4.0 to 2.5 billion years ago. Over these roughly two billion years, the Earth accreted from planetesimals, and developed its core, mantle, oceans, and earliest crust. The nature of the Hadean crust can be explored only indirectly as none has survived. Archean cratons preserve a legacy of crust with deep mantle lithosphere keels composed of greenstones and high grade felsic gneiss. Toward the end of the Archean, these rock suites gave way to continental crust we’d recognize today. Archean cratons are the oldest pieces of continental crust on the planet and form the nuclei of many continents, as shown in the image depicting the cratonic nuclei of Africa (bright green), which stand out against the background of younger crust. To quote the Beatles, “it has been a long and winding road!”

v20n2 From the Editors

By Janne Blichert-Toft, Sumit Chakraborty, Tom Sisson, and Esther Posner | April, 2024

Subduction, where one plate dives beneath another, controls long-term whole-Earth cycling of rocks, fluids, and energy. Plates subduct faster than they heat up, making them the coldest parts of the Earth’s interior. Fluids released from these cold plates rise into hotter overlying rocks, forming magma that feeds surface volcanism. Cold deep conditions associated with subduction complemented by hot shallow conditions under volcanic arcs are reflected in the presence of pairs of metamorphic belts, representing sites of ancient subduction. This issue of Elements guides readers through a premier example of paired metamorphism: the Cretaceous SanbagawaRyoke metamorphic pair of Japan. Estimates of pressure, temperature, the age and duration of metamorphism, and the tectonic framework in which metamorphism took place help us to develop quantitative models—both for the evolution of SW Japan and subduction systems in general.

v20n1 From the Editors

By Becky Lange, Janne Blichert-Toft, Sumit Chakraborty, Tom Sisson, and Esther Posner | February, 2024

Extraterrestrial organic matter—organic molecules beyond our planet—sparks curiosity and fuels the search for their nature, origin, and distribution due to their importance for cosmochemistry and for life. From the dusty surfaces of asteroids and the icy realms of comets, to planetary systems being born, galaxies far away, and atmospheres of exoplanets, scientists have uncovered a cosmic cocktail of carbonbased compounds. These extraterrestrial molecules, akin to the very essence of life on Earth, serve as enchanting hints that the building blocks of life may not be exclusive to our planet. Meteorites, cosmic dust, and other planetary samples carry the fingerprints of “out of this world” organic chemistry, which are, in a sense, cosmic secrets encoded in carbon compounds. As telescopes peer into distant locations and space rovers explore different landscapes, the quest for the origin of organic matter, building blocks of life, intensifies. Analytical developments and access to some of the most pristine organic-rich planetary samples are driving scientists into new frontiers. Thus, more groundbreaking revelations are inevitable.