Gems

Emmanuel Fritsch and Benjamin Rondeau – Guest Editors

Table of Contents

Most gems are natural minerals, which, although scarce and small, have a major impact on society. Their value is directly related to proper identifi cation. The determination of the species is key, of course, and must be done nondestructively. This is where classical tools of mineralogy come into play. However, other issues are paramount: Has this gem been treated? Is it natural or was it grown in a laboratory? For certain varieties, be ing able to tell the geographical provenance may enhance value considerably. These issues neces sitate crosslinking the formation of gems with their traceelement chemistry. These unusual mineralogical and geochemical challenges make the specificity of gemology, a new and growing science, one of the possible futures of mineralogy.

Gemology: The Developing Science of Gems

- Gem Formation, Production, and Exploration: Why Gem Deposits Are Rare and What is Being Done to Find Them

- The Geochemistry of Gems and Its Relevance to Gemology: Different Traces, Different Prices

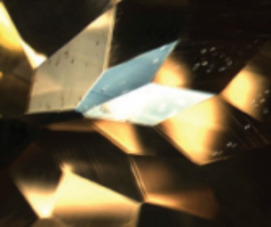

- The Identification of Faceted Gemstones: From the Naked Eye to Laboratory Techniques

- Seeking Low-Cost Perfection: Synthetic Gems

- Laboratory-Treated Gemstones

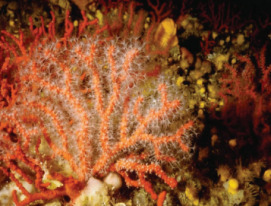

- Pearls and Corals: “Trendy Biomineralizations”

Excalibur Mineral Corporation

GAAJ-ZENHOKYO Laboratory

GemNantes

Gemological Institute of America

RockWare

Savillex

Smart Elements

Thermo

v5n4 Mineral Magnetism: From Microbes to Meteorites

Guest editor: Joshua M. Feinberg (University of Minnesota) and Richard J. Harrison (University of Cambridge)

Magnetic minerals are ubiquitous in the natural environment. They are also present in a wide range of bio logical organisms, from bacteria to human beings. These minerals carry a wealth of information encoded in their magnetic properties. Mineral magnetism decodes this information and applies it to an ever increasing range of geoscience problems, from the origin of magnetic anomalies on Mars to quantifying variations in Earth’s paleoclimate. The last ten years have seen a striking improve ment in our ability to detect and im age, with higher and higher resolu tion, the magnetization of minerals in geological and biological samples. This issue is devoted to some of the most exciting recent developments in mineral magnetism and their ap plications to Earth and environmental sciences, astrophysics, and biology.

Mineral Magnetism: Providing New Insights into Geoscience Processes By Richard J. Harrison (University of Cambridge) and Joshua M. Feinberg (University of Minnesota)

- Geodynamo History Preserved in Single Silicate Crystals: Origins and Long-Term Mantle Control John A. Tarduno (University of Rochester)

- Magnetism of Extraterrestrial Materials Pierre Rochette CEREGE), Benjamin P. Weiss (MIT), and Jérôme Gattacceca

- Rain and Dust: Magnetic Records of Climate and Pollution Barbara A. Maher (Lancaster University)

- Magnetic Nanocrystals in Organisms Mihály Pósfai (University of Pannonia) and Rafal E. Dunin-Borkowski (Technical University of Denmark)

- Crustal Magnetism, Lamellar Magnetism and Rocks That Remember Suzanne A. McEnroe, Karl Fabian, Peter Robinson, Carmen Gaina and Laurie L. Brown

- Scientific Exploration of the Moon (February 2009)

- Bentonites – Versatile Clays (April 2009)

- Gems (June 2009)

- Mineral Magmatism: From Microbes to Meteorites (August 2009)

- Gold (October 2009)

- Metal Stable Isotopes: Signals in the Environment (December 2009)

Download 2009 Thematic Preview