Urban Geochemistry

W. Berry Lyons and Russell S. Harmon – Guest Editors

Table of Contents

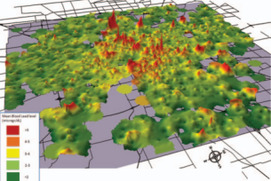

By 2030, about 60% of the human population will live in cities. Clearly, anthropo genic activities in urban environments affect geochemical cycles, water resources, and the health of ecosystems and humans globally. past practices are still having biogeochemical impacts today, and in many cases remediation is needed. Both natural and man made disasters greatly change the geochemistry of urban areas. Understanding past impacts can aid in future disaster planning. an increased awareness of the geochemical and mineralogical effects of urbanization on geo chemical cycling will aid urban planners in the effort to make urban develop ment sustainable.

- Geochemistry and the Sustainable Urban Environment

- Urban Geochemistry: The Legacy Problem

- The Impact of Urban Development on Hydrology and Geochemistry

- Ecological and Biogeochemical Dynamics in Urban Settings: Lessons from Long-Term Ecological Research

- Urban Geochemistry and Human Health

- Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Urban Settings

- Environmental and Medical Geochemistry in Urban Disaster Response and Preparedness

Bruker

Bruker Nano

CAMECA

FEI

Excalibur Mineral Corporation

Geochemist’s Workbench

McCrone Microscope and Accessories

MEDGEO 2013

Rigaku

Savillex

SPECTRO

v9n1 ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF ISOTOPE GEOCHRONOLOGY

Guest Editors: Daniel J. Condon (British Geological Survey) and Mark D. Schmitz (Boise State University)

In 1913, Frederick Soddy’s research on the fundamentals of radioactivity led to the discovery of “isotopes.” That same year, Arthur Holmes published his now famous booklet The Age of the Earth. Combined, these two landmark events established the field of science we know as “isotope geochronology.” Today, isotope geochronology underpins much of our knowledge of the absolute age of minerals and rocks, and the records they contain. This field is constantly evolving, reflecting and responding to scientific drivers that require more highly resolved timescales, the microscopic analysis of smaller zoned minerals, or the generation of robust data sets in novel materials. This series of articles provides perspectives on the state of the art in the field of radioisotope dating—from the challenges of dating the Solar System’s oldest materials to resolving the record of Quaternary climate change, and the four and a half billion years in between.

- One Hundred Years of Isotope Geochronology, and Counting Daniel J. Condon (British Geological Survey) and Mark D. Schmitz (Boise State University)

- Accuracy and Precision in Geochronology Blair R. Schoene (Princeton University), Daniel J. Condon (British Geological Survey), Leah E. Morgan (SUERC, Scotland), and Noah M. McLean (British Geological Survey)

- High-Precision Geochronology Mark D. Schmitz (Boise State University) and Klaudia F. Kuiper (VU University Amsterdam)

- High-Spatial-Resolution Geochronology Alexander A. Nemchin (Curtin University), Matthew S. A. Horstwood (British Geological Survey), and Martin J. Whitehouse (NORDSIM, Sweden)

- Dating the Oldest Rocks and Minerals in the Solar System Yuri Amelin (Australian National University) and Trevor R. Ireland (Australian National University)

- Time Constraints and Tie-Points in the Quaternary Period David A. Richards (Bristol University) and Morten B. Andersen (Bristol University)

- Revolution and Evolution: 100 Years of U–Pb Geochronology James M. Mattinson (University of California, Santa Barbara)

- Impact! (February 2012)

- Minerals, Microbes, and Remediations (April 2012)

- Fukushima Daiichi (June 2012)

- Granitic Pegmatites (August 2012)

- Rare Earth Elements (October 2012)

- Urban Geochemistry (December 2012)

Download 2012 Thematic Preview

- One Hundred Years of Geochronology (February 2013)

- Serpentinites (April 2013)

- The Mineral-Water Interface (June)

- Continental Crust at Mantle Depths (August 2013)

- Nitrogen and Its (Biogeocosmo)Chemical Cycling (October 2013)

- Garnet: Common Mineral, Uncommonly Useful (December 2013)

Download 2013 Thematic Preview